Last week, July 25th, was the day of Antifascist Pasta; the day that celebrates the Italian resistance to Fascism and Mussolini’s attempt to convince his countrymen to eat rice instead of pasta, a beloved food staple then and now, it goes without saying. Food connects us to our ancestors, and in this case specifically to my grandfather, but not perhaps as you’d think.

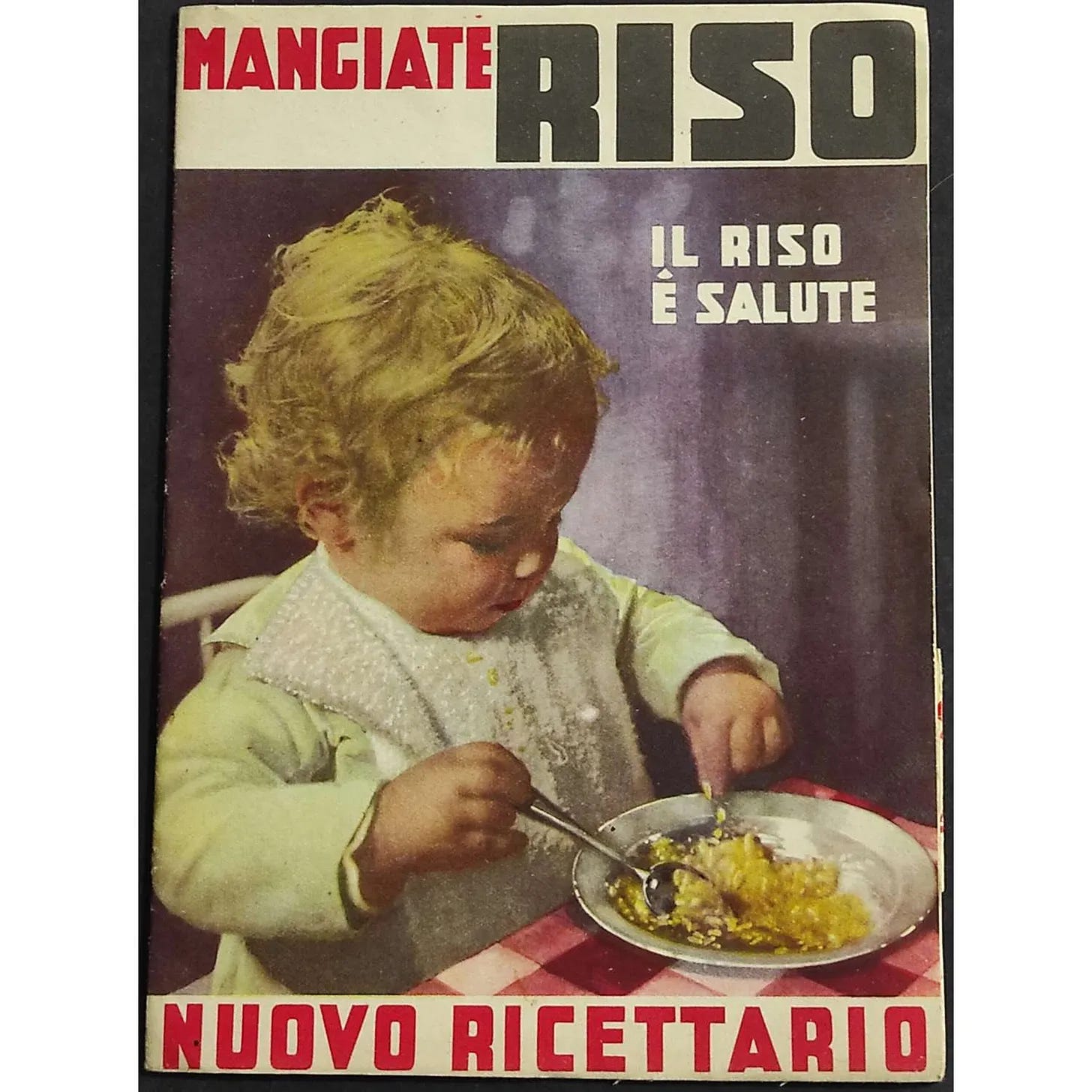

I’ll circle back to the personal and begin with the world history. Mussolini, seeking to create a self-contained economy and limit reliance on foreign imports, wanted the country to move away from flour. Since the Northern part of the country grew and ate rice, rice became the campaign’s choice of substitution. The remarkable part of this history is not so much Mussolini’s attempt to alter Italian cuisine for political and economic ends—food has been used as warfare for centuries—but the fact that being neither a dictator nor a rather scary man made him successful in doing so. People resisted. They would only be pushed so far. Italians drew the line at pasta.

I was inspired to write this essay by Emiko Davies’ “The history of Italy's partisans through food,” which gives an excellent dive into this topic, as well as L’Appetito’s “Angels in Heaven Eat Nothing but White Flour.” Davies relies heavily on the book, Partigiani a Tavola: Storie di Cibo resistente e ricette di libertà, (“Partisans at the Table: Stories of food of the resistance and recipes of freedom”) by Elisabetta Salvini and Lorena Carrara, which I’ve started reading (in Italian, so it may take me a bit!) because the fact that food is so much more than physical sustenance is very dear to my heart: Food is culture, it’s connection, it’s politics, it’s spiritual, and as we’ll talk about in this essay, it’s resistance.

As the daughter of Southern Italian immigrants, I never ate risotto growing up. In fact, I was an adult before I really came into contact with the dish. I’m sure I’d seen it in restaurants and on menus, but if I did, I simply glazed over it. Rice? Why would I eat a bowl of rice when I could eat a bowl of pasta? I didn’t understand at the time that my disinterest was rooted in place and history. Risotto is a Northern Italian dish, where, as I’ve already mentioned, rice is a staple; in the mezzogiorno, where my family is from, pasta is king. My aversion to risotto and adoration of pasta was, unbeknownst to me, a claiming of my Southern Italian heritage, as well as, according to the story of antifascist pasta, an act of resistance.

Growing up, pasta with butter and cheese, the ingredients for antifascist pasta, was a go-to part of the culinary pantheon of “peasant food” we ate without awareness of its origins. Pasta with potatoes. Pasta with peas. Pasta with beans. Pasta with simply oil and garlic. And pasta with butter and parmesan. These were the foods our parents and grandparents ate, altering what went into the pasta based on the season and what was available, but most importantly, based on what they could grow or afford. Pasta with butter and cheese remains a staple when I need to whip up a quick, hearty and nutritious meal. (Use good pasta made simply from durum wheat, as well as grass-fed butter, and you’ve got something wholesome on the dinner plate.) It’s not only a delicious dish, it has, as with most traditional foods, a history.

Davies notes in her essay that Italians, mainly of the South, were introduced to pasta after the First World War and through the mass emigration that occurred in that era. In America, Italians of different regions mingled, creating an Italian cultural identity long before Italians themselves did. The unification of 1861 was a unification on paper only. The north and south remained two different countries in their identities, hearts and minds, as in many ways they remain today. But in America, Sicilians, Neapolitans and Milanese lived side-by-side, mingling their culinary peculiarities, and a love of pasta.